Why Draw?

What's the Point?

In an age when almost everyone is carrying a half-decent camera/phone everywhere they go, it seems appropriate to ask “Why draw?” Drawing is time-consuming, too slow to capture changing scenes and usually a messy process. It’s so much quicker, easier and cleaner to whip out your phone, point and shoot. If your phone’s photo gallery is anything like mine, it is likely a mishmash of casual pics of maybe interesting scenery, family and friends, posters on noticeboards that have possibly relevant information to follow up later, as well as screenshots of bank payments and online acknowledgements that would otherwise disappear into the void. So I ask again “Why draw?”

A clue is perhaps in the proliferation of such images that we snatch from the whirlwind of information around us. Drawing might offer some respite from that never-ending bombardment of mostly useless stuff.

But there’s a deeper point that’s often not recognised. Sitting down to draw something starts to make it clear just how much we don’t see in our ordinary modes of engaging with the world. Drawing a scene requires full attention and offers a chance to see things far more clearly and fully than we ordinarily do. Interestingly, people who are skilled at drawing spend much more time looking at their subject than they do at the paper on which they are drawing.

In my everyday mode, as I navigate through what are mostly familiar surroundings and circumstances, my vision brushes over the objects in my environment. Once something is recognised, there is no further need for looking. So I don’t really see things then, or at least my envisaging of them is just as superficial as it needs to be for me to find my way between them.

When I am looking at an object or a scene when drawing it, there’s a lot more there than it seems at first glance. It becomes apparent that seeing and recognition are extremely sophisticated processes that we mostly take for granted. Producing a drawing that has half-decent resemblance to the original is quite a task.

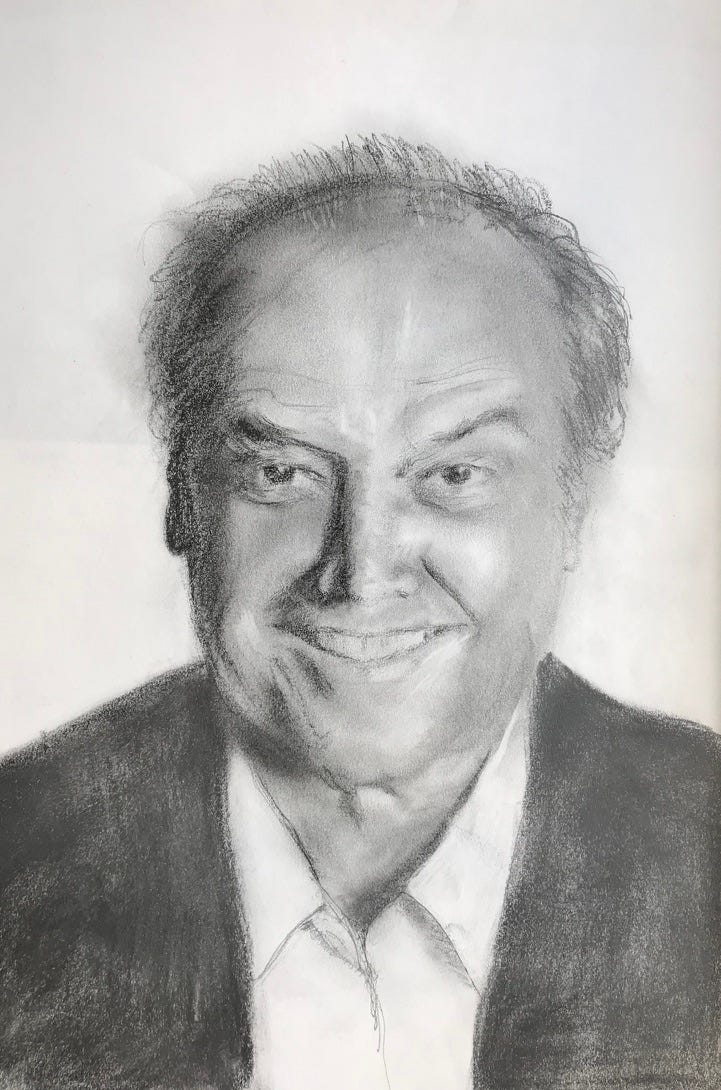

A drawing is really an optical illusion, giving the viewer an impression of the scene from which it is taken. For one thing, the drawing is on a flat surface, two-dimensional, and yet it can give the impression of a solid object, a three-dimensional scene. Some drawings and artworks do this so convincingly that they can fool the eye (“trompe l’oiel”) into believing that they are three-dimensional.

A Peek Under the Hood of Vision

We don’t really see things; rather what we see is the pattern of light reflected from those things. The automatic visual processing that goes on behind the eyes decodes those patterns to suggest a great deal about the location and shape of the object(s), even what they might be made of. In a drawing, the clues to solidity and curvature mainly come from the arrangement of light and shade and how gradually or abruptly they transition from one to the other.

Like almost everything else in our mental realm, a drawing is a model of its subject - always an imperfect, incomplete representation. It’s enough for a drawing to give an impression of the subject, allowing the viewer’s visual sense to fill in the blanks. Often a drawing is all the more successful for leaving something to the imagination. Part of the art of drawing is knowing when to stop, rather than overworking the piece.

Process, not Product

But the outcome isn’t so much the point as the process of drawing. Sitting down to draw something that you might not otherwise give a second glance is a discipline that makes you slow down and look properly. You start to appreciate the immediacy of real things, beneath the glossing over that we inevitably do in everyday engagement with the physical world. So taking the time to draw is a kind of meditative opportunity to be in the presence of reality and enjoy a kind of mental vacation without the need to travel to exotic places.

Most of us won’t be sufficiently persuaded by my points above to take up drawing. Most young children draw prolifically and without a care for how ‘good’ or ‘bad’ the outcome is - they just revel in the creative act and we vicariously delight in it with them. But as we grow most of us start to judge the outcomes harshly and become discouraged enough to give up on drawing as a means of expression. We’ve forgotten the enjoyment of the process. I have a vivid memory of my granddaughter at the age of three, chattering away as she drew at the kitchen table, mostly in her then favourite colour of pink, totally absorbed in the process and free of the deadening effect of judgement. She still draws, just with less chattering and more privacy. Whether she’ll continue into teens and adulthood remains to be seen. But I know for myself in returning to drawing in mid-life and beyond that it is a route to deep insights, not only into the objects being drawn but very much into the drawer, that is myself and my mental processes that I usually take for granted.

Chief among these illuminations is the process of learning, something normally transparent to us in the midst of it. It took me many years of learning and teaching Physics at school and university to realise some of the deep subtleties of nature and the process of learning about it. I found those same insights became apparent almost immediately in the much more accessible process of learning to draw. For instance, that our predominant tools of trade in engaging with the world are representative in nature - that is, models of reality that can mimic the behaviours we observe out there, but only in a very limited way. As much as a mathematical equation used in Physics is a model, so too is a drawing and both are equally the outcome of creative acts. We too easily forget this, and what is most overlooked is that teaching and learning are not processes of information delivery and absorption, but are deeply creative in nature - even with subjects as prosaic as mathematics or physics.

So rather than thinking that there are some people who are creative and then there’s the rest of us, be aware that creativity is what has got you here and that it’s maybe been overlooked as the essential life force that it is. That’s something to be celebrated in its unearthing and dusting off. When you know the true nature of what you’ve been doing all along, it can transform the process and the quality of its outcome.

Drawing is one way to take yourself through the spaces of paying more attention to what is in front of you than to your preconceptions or abstractions about it, being in its presence, allowing for some wonderment and making an expression to represent it, unique to your encounter with it. It may not be the only way, but it is immediately available to almost anyone who cares to try, it can be applicable to almost any subject and is for all intents and purposes effectively inexhaustible.